Bonsai Dragon & Deadwood Tips

Do you like deadwood on bonsai? If so, are you in the let’s not overdo it camp, or are you a proponent of the no-holds-barred, go for broke approach that’s expressed loud and clear on Masahiko Kimura's Dragon? The no-holds-barred deadwood approach by the grand deadwood innovator and master, Masahiko Kimura. He named the tree Dragon. The photo is from Bonsai Today issue 2 (long out of print). It also appeared in The Bonsai Art of Kimura (also long out of print).

The no-holds-barred deadwood approach by the grand deadwood innovator and master, Masahiko Kimura. He named the tree Dragon. The photo is from Bonsai Today issue 2 (long out of print). It also appeared in The Bonsai Art of Kimura (also long out of print).

Or maybe you don’t like deadwood at all. If so, you might want to stick with deciduous or tropical trees, where deadwood is a lot less common. So you won’t be tempted.

No need for deadwood on this famous tropical masterpiece. It's a Ficus microcarpa by Huang, Ching-Chi of Taiwan.

If you stray into conifers (especially junipers) where most trees these days have experienced at least some carving, sooner or later you'll most likely find yourself succumbing to the urge.

Maybe it will be just a small jin on a little branch stump. Or a modest shari to cover an accidental wound on a trunk (that happened to me just the other day).

This is where it starts, but if you’re not careful some day you’ll end up carving trees that look something like this. Well. maybe not really like this, but you get my point.

This photo is one of many that were taken by Andres Bicocca at the 2017 European Bonsai San Show in Saulieu France. None of the trees or artists are identified (no blame, they were no doubt taken on the fly and I’m just happy to have them). The tree might be called sculptural. It's a look that seems to offend some people. The primary complaint is that it looks plastic (I think Walter Pall used that term). Another is that it doesn't look like tree. As John Naka said "Make your bonsai look like a tree".

This photo is one of many that were taken by Andres Bicocca at the 2017 European Bonsai San Show in Saulieu France. None of the trees or artists are identified (no blame, they were no doubt taken on the fly and I’m just happy to have them). The tree might be called sculptural. It's a look that seems to offend some people. The primary complaint is that it looks plastic (I think Walter Pall used that term). Another is that it doesn't look like tree. As John Naka said "Make your bonsai look like a tree".

John Naka, the Dean of American bonsai with his famous Goshin. As you can see, Mr Naka used ample deadwood - even whole trees in his forest are dead - but the planting still looks natural. Photo by Cheryl Manning.

John Naka, the Dean of American bonsai with his famous Goshin. As you can see, Mr Naka used ample deadwood - even whole trees in his forest are dead - but the planting still looks natural. Photo by Cheryl Manning.

François Jeker, deadwood artist and author of Bonsai Deadwood does some of the most detailed and natural looking carving anywhere.

François Jeker, deadwood artist and author of Bonsai Deadwood does some of the most detailed and natural looking carving anywhere.

One mistake beginners (and others) make, is to carve too much too soon. If you jump right in without much experience (or without a plan) and start peeling and gouging away, you can do a lot of damage in just a few minutes (take it from someone who knows first hand).

These illustrations by François give you a glimpse into the depth of his understanding of deadwood (and of his talent as an illustrator). They originally appeared in Bonsai Today issue 103.

These illustrations by François give you a glimpse into the depth of his understanding of deadwood (and of his talent as an illustrator). They originally appeared in Bonsai Today issue 103.

Before you start carving, it's critical to know where the living veins are. If you damage a vein that supports a branch or even a whole side of the tree (or even the whole tree) you can easily end up with dead branches or worse, a dead tree.

Living veins are roughly analogous to blood vessels (or highways) that move water and nutrients from the roots to the tops and vice versa. Some elements go up from the roots to feed the tops and others go down from the foliage to feed the roots - an ongoing and critical exchange (this exchange is interrupted during dormancy).

Close up of live veins on a Rocky mountain juniper that belongs to Michael Hagedorn. I borrowed the photo from a post on Michael's Crataegus Bonsai blog titled Juniper Live Veins and How They Move.

Close up of live veins on a Rocky mountain juniper that belongs to Michael Hagedorn. I borrowed the photo from a post on Michael's Crataegus Bonsai blog titled Juniper Live Veins and How They Move.

Live veins aren’t always obvious, though they often bulge a bit. So if you find a bulge running the length of the trunk with crevices or indents on either side, then you’ve located a live vein (live veins also run out branches).

Another way to locate living veins is to gently scrape away loose dead bark. If the cambium layer underneath is alive (green) then stop scraping. If it’s not alive, continue to scrape the bark away and expose the deadwood underneath. Just be sure to stop when you come to a live area. Now you’re on your way to successfully locating and distinguishing living veins from from dead tissue. It's these area with dead tissue that are okay for carving.

This almost otherworldly carving job belongs to Harry Harrington. The tree is a Yew (Taxus baccata). We’ve shown it a couple times on Bonsai Bark, but I think it’s worth another look. The built to fit pot is by Victor Harris of Erin Pottery.

This almost otherworldly carving job belongs to Harry Harrington. The tree is a Yew (Taxus baccata). We’ve shown it a couple times on Bonsai Bark, but I think it’s worth another look. The built to fit pot is by Victor Harris of Erin Pottery.

Once you’ve located dead tissue, feel free to carve it. But as you’re peeling away the bark that's covering the dead tissue, be careful not to peel bark that’s covering live tissue. This may sound simple, but it takes some practice and judicious care.

There’s much more on the art of carving, though if you proceed with caution and remember to locate the living veins and take care not to damage them, you might be successful.

Olive deadwood by Harry Harrington. You can create deadwood that looks old with skillful carving and finishing, but only nature and time can create aged bark .

Almost forgot... Not all carving is done on tissue that is already dead. You can also intentionally kill living wood by carving it. This is okay if you know what you're doing and you make sure to save the essential live veins you need to support the parts of the tree you want to stay alive and healthy.

The Softer Side of Bonsai

It's good to have friends. Especially ones who think of you when they see something related to bonsai in a national newspaper. In this case the friend is Greg McNally, a fellow tree lover and the owner of the Northern Vermont land where I dig most of my larches

The link Greg sent me is from The Washington Post and though it has little do with larches or other trees it does have something to do with bonsai. Or at least an art that is intimately related to bonsai

But rather than me going on about it, we'll let Adrian Higgins, the author of the article tell the story (well, just the first few paragraphs)...

Here's Adrian's caption... "Although bonsai trees can appear immutable, kusamono compositions mark the seasons, here the arrival of the early spring blooms of the epimedium hybrid Niveum." Like this caption the ones below are also by Adrian Higgins. (photo by Young Choe)

One reason for this is that although bonsai is a popular and commercialized hobby, there are just a handful of kusamono virtuosos in the United States, none more accomplished than Young Choe, a Korean American horticulturist from Ellicott City.

"Horticulturist Young Choe brings an American flair to the Japanese artform of kusamono. This composition includes the wildflower Indian pink, sedge and the perennial Culver’s root." (Photo by Young Choe)

"Most of the subjects are grasses and perennials, but Choe sometimes uses shrubby material. This wild rose was raised from seed and took six years to bloom." (Photo by Young Choe)

"Her creations — unexpected, essential and surprisingly haunting — take common plants and elevate them as living subjects of delight and desire. A pennisetum grass you might barely notice in the office park becomes kinetic sculpture; common cranesbill is transformed into a grove of flowers; and the trillium of the woodland floor is placed on Choe’s pedestal. 'I love to show people how beautiful they are,' she said."

For the rest of the article visit The Washington Post.

"To Create Outstanding Bonsai, You Need to Have an Understanding of Psychology..."

How did he do this? Because you can't see any soil, you might wonder if this one is a flowering air plant. Though no explanation (nor plant variety) is given, my guess is that there is a pocket of soil nestled out of sight in this piece of driftwood

How did he do this? Because you can't see any soil, you might wonder if this one is a flowering air plant. Though no explanation (nor plant variety) is given, my guess is that there is a pocket of soil nestled out of sight in this piece of driftwood

One of many things that Robert Steven is know for are his breaks with bonsai convention. Just when you think he has achieved some mastery of a style he's off trying something else

The photos shown here are from Robert's ArtFest on his Missions and Legends 2020 (Facebook)

Continued below...

Here's Robert's caption with this one... "Nature holds the perfect key to aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual balance; breaking its balance will bring disaster!"

Here's Robert's caption with this one... "Nature holds the perfect key to aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual balance; breaking its balance will bring disaster!"

Continued from above...

Robert's ArtFest Quote of Today (April 4th, 2020)

"To create outstanding bonsai, you need to have an understanding of psychology, human behavior, and the little shortcuts, the little quirks, in the way people operate; then you can use them to make it easier for people to engage with your creation."

Robert's caption "Critics and curators are failed artists." A little harsh but being outspoken comes with the territory

Robert's caption "Critics and curators are failed artists." A little harsh but being outspoken comes with the territory

This one seems a bit more conventional,

though the pot might have something to say about that

A metaphor for bonsai? You'll have to click over to read Robert's comment

A metaphor for bonsai? You'll have to click over to read Robert's comment

Robert with one of his unique creations

Robert with one of his unique creations

Small Bonsai - Muscular Trunks & Colorful Pots

Bright yellow is a strong color, but I think this tree can handle it. The dense foliage and sturdy trunk are the keys. The artist is Tomohiro Masumi. No variety is given

Bright yellow is a strong color, but I think this tree can handle it. The dense foliage and sturdy trunk are the keys. The artist is Tomohiro Masumi. No variety is given

All the photos in this post, which we originally featured almost two years ago, are from Tomohiro’s timeline. The only text is “Takao Koyo pots at Shuga-ten.”

Another bright yellow pot and an even stronger trunk. Again no variety is given, but the leaves are easy to identify as Japanese maple...

Another bright yellow pot and an even stronger trunk. Again no variety is given, but the leaves are easy to identify as Japanese maple...

Another strong pot and another maple, though this time it's a Trident. You can recognize Trident maples by their three pointed leaves (thus the name). The impressive nebari has a distinctively Trident look as well

Another strong pot and another maple, though this time it's a Trident. You can recognize Trident maples by their three pointed leaves (thus the name). The impressive nebari has a distinctively Trident look as well

Is it just me, or do the color of the tree and pot together seem a little dissonant. Or perhaps a little dissonance isTomohiro’s intention

Is it just me, or do the color of the tree and pot together seem a little dissonant. Or perhaps a little dissonance isTomohiro’s intention

A white snake invasion, or just a bench full of Tomohiro Masumi's little trees (mostly junipers) with fresh lime sulfur?

A white snake invasion, or just a bench full of Tomohiro Masumi's little trees (mostly junipers) with fresh lime sulfur?

Tomohiro Masumi loving bonsai

Saikei Bonsai - Creating a Planting with a Deep Ravine

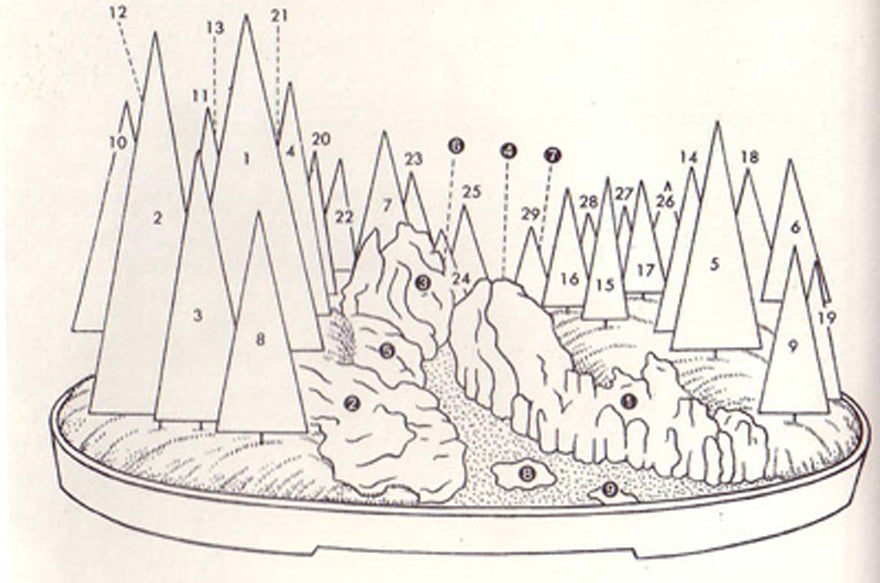

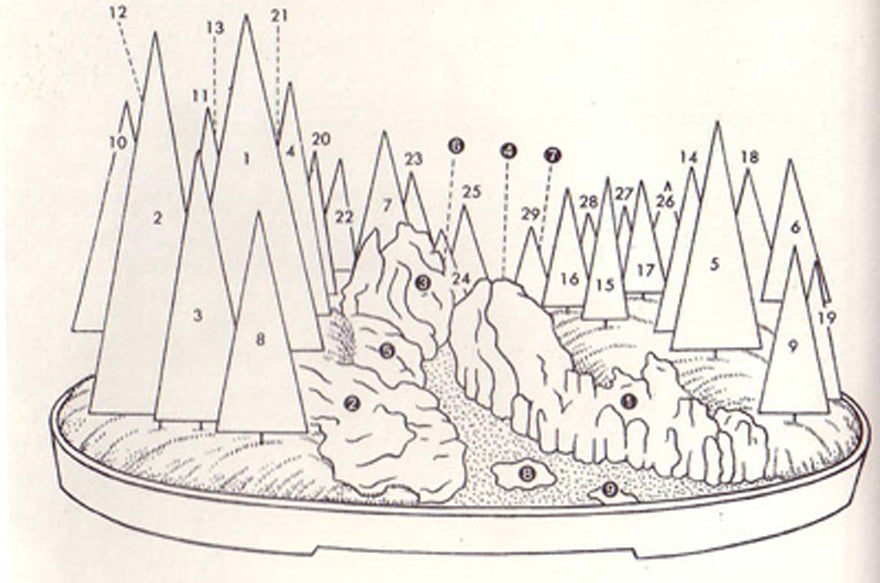

This planting from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic is quite similar to the planting on the cover (below): same trees (cryptomeria), same (or nearly the same) pot and somewhat similar rocky ravine separating two tree and moss covered areas. The main difference is that this one shows a deep ravine. The rocks that define it represent tall vertical cliffs

This planting from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic is quite similar to the planting on the cover (below): same trees (cryptomeria), same (or nearly the same) pot and somewhat similar rocky ravine separating two tree and moss covered areas. The main difference is that this one shows a deep ravine. The rocks that define it represent tall vertical cliffs

Today we're dialing way back to 2010 (our second year for Bonsai Bark) and revisiting one of our favorite and most popular series of posts. I've left my original text almost completely intact, with only minor editing. Stay posted for more...

How to create a deep ravine saikei...

The purpose of this section from the Toshio Kawamoto's original is to show how to create a deep ravine saikei, just like the one in the photo above. In fact, if you look at the drawings, it’s almost as if the author is inviting you to duplicate his work

Front schemata. The pot is 27″ x 19″ (69cm x 48cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 29 cryptomeria that range from 4″ to 14″ (10cm to 36cm) tall and 9 river rocks. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use akadama or an akadama mix for conifers). The other materials are moss, river sand and white sand

Front schemata. The pot is 27″ x 19″ (69cm x 48cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 29 cryptomeria that range from 4″ to 14″ (10cm to 36cm) tall and 9 river rocks. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use akadama or an akadama mix for conifers). The other materials are moss, river sand and white sand

Bird’s eye view. Notice how the opening in front is off center and slants and curves as it goes back. If it were directly centered and straight it would appear contrived. Notice also how the ravine narrows and curves around and disappears from sight and then opens up into a pool. Viewed from the front, this creates a sense of mystery and the appearance that it just goes on and on into a vast landscape, rather than being restricted to a very finite pot

Bird’s eye view. Notice how the opening in front is off center and slants and curves as it goes back. If it were directly centered and straight it would appear contrived. Notice also how the ravine narrows and curves around and disappears from sight and then opens up into a pool. Viewed from the front, this creates a sense of mystery and the appearance that it just goes on and on into a vast landscape, rather than being restricted to a very finite pot

I found this old out-of-print classic* at Green Apple Books in San Franscisco for ten dollars (minus my family discount – see disclaimer below). It was in near perfect condition after more than forty years (now more than 50 years... copyright 196, Kodansha International). The original price was $6.95 (hardcover no less).

I found this old out-of-print classic* at Green Apple Books in San Franscisco for ten dollars (minus my family discount – see disclaimer below). It was in near perfect condition after more than forty years (now more than 50 years... copyright 196, Kodansha International). The original price was $6.95 (hardcover no less).

BTW: Green Apple is one of the best surviving used/new independent bookstores anywhere (disclaimer: my son-in-law is part owner, but this takes away nothing from the fact that it’s a great place and an institution in San Fransisco)

John Palmer, founder of Bonsai Today and Stone Lantern Publishing mentioned this book to me years ago. I think he was hoping that it would show up back in print, or perhaps he was entertaining ideas of reprinting it himself (memory doesn’t always serve). Years later I got lucky and stumbled upon it

*To answer your question in advance, no we do not have any for sale. There are however, several for sale online at a range of prices (be careful). All you have to do it google it.

The Practice of Naming Bonsai... Whirlpool Is Obvious Enough, but It's Not Always That Simple

Koryo is the given name of this Japanese maple. No translation is given, but one possibility in 'consideration' as in 'worthy of consideration,' but that's just a guess on my part. Its estimated age is 120. The photo is from The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama, Japan

Koryo is the given name of this Japanese maple. No translation is given, but one possibility in 'consideration' as in 'worthy of consideration,' but that's just a guess on my part. Its estimated age is 120. The photo is from The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama, Japan

In North America most people don't name their bonsai. Or if they do, I don't know about it. However, in Japan naming seems to be a fairly common practice. Especially with very old trees. Or so it seems...

This morning I went through a couple dozen photos from The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum and found five that had names listed. All five are over 100 years old and my guess is that this is no coincidence. As top quality bonsai age and develop more and more character and fame they become worthy of names (you might imagine this has to do with repeatedly showing up in top shows and receiving high accolades)

Koryo, a closer look

Koryo, a closer look

This Japanese black pine is called Seiran, which in this case it might be 'star.' Though if you really care, you might look up the Kanji (Omiya shows it) and do your own research. The estimated age is 120 years

This Japanese black pine is called Seiran, which in this case it might be 'star.' Though if you really care, you might look up the Kanji (Omiya shows it) and do your own research. The estimated age is 120 years

Seiran, a closer look

Seiran, a closer look

Seijaku is the name given to this Japanese white pine. Nothing came up in my cursory search under Seijaku, but looking at the Kanji given with Omiya's name, 'silence' might work (please don't take this to the bank, I don't read Kanji and can only guess)

Seijaku is the name given to this Japanese white pine. Nothing came up in my cursory search under Seijaku, but looking at the Kanji given with Omiya's name, 'silence' might work (please don't take this to the bank, I don't read Kanji and can only guess)

Seijaku's estimated age is 200 years

Seijaku's estimated age is 200 years

This Japanese black pine with its trunk fused to a rock is called Zuiko. You might want to do your own research (it's complicated). The tree's estimated age is 120 years

This Japanese black pine with its trunk fused to a rock is called Zuiko. You might want to do your own research (it's complicated). The tree's estimated age is 120 years

Zuiko, close up

Zuiko, close up

Saving the granddaddy for last. It's Japanese white pine called Uzushio with an estimated age of 500 years. There doesn't seem to be any ambiguity about the name... Uzushio means 'whirlpool'

Saving the granddaddy for last. It's Japanese white pine called Uzushio with an estimated age of 500 years. There doesn't seem to be any ambiguity about the name... Uzushio means 'whirlpool'

Whirlpool, close up

Whirlpool, close up

Here's a photo from a post we did in 2015 on this same tree. In that post I called it 'Whirlpool Dancer' (I'm not sure where I got the Dancer part). It is also featured in our Masters Series Pine book (see just below) in a chapter titled, 'Jewel to Whirlpool'

Here's a photo from a post we did in 2015 on this same tree. In that post I called it 'Whirlpool Dancer' (I'm not sure where I got the Dancer part). It is also featured in our Masters Series Pine book (see just below) in a chapter titled, 'Jewel to Whirlpool'

Masters Series Pine Book

Masters Series Pine Book

Available at Stone Lantern

Can You Tell Penjing from Bonsai?

I think all three of the trees in this Penjing water planting above would qualify as bonsai on their own and there are some bonsai plantings that might share some rock features with this one

I think all three of the trees in this Penjing water planting above would qualify as bonsai on their own and there are some bonsai plantings that might share some rock features with this one

The overall arrangement above is easy to identify as Penjing, No doubt the low white tray helps, but there's something a little more difficult to put your finger on. Perhaps the way the rocks are put together and more importantly, the overall sense of scale and wild ruggedness that is common in Penjing, which seems to specialize in these panoramic landscapes

Not that there aren't bonsai that head in that direction, especially some saikei, but Chinese (and perhaps Vietnamese) penjing seems to say it best. And of course there are plenty of Penjing that don't emphasize the landscapes as much as the individual trees, some of which are almost indistinguishable from Japanese style bonsai

So in answer to the question posed in the title and because I'm in no way an authority on the topic, I'll take the easy way out and leave it up to you. And if you need some help, perhaps you could consult someone like Robert Steven, a person who has spent a long time studying, practicing, teaching and writing about bonsai and penjing arts (stay posted)

This one, which happens to one of my favorite Penjing plantings, seems even larger in scale as the one above and also has a couple human features that set it apart and enhances the feeling of a vast natural setting. These little human or human structure figurines (like boats and huts) are common in certain types of Penjing and much less common in bonsai, though you may see them in some saikei plantings

This one, which happens to one of my favorite Penjing plantings, seems even larger in scale as the one above and also has a couple human features that set it apart and enhances the feeling of a vast natural setting. These little human or human structure figurines (like boats and huts) are common in certain types of Penjing and much less common in bonsai, though you may see them in some saikei plantings

My apologies for lack of attribution. I found these two Penjing landscapes several years ago on fb and featured them on Bonsai Bark (though the text is all new today). I'm not so sure that our source (Pham Thai Bihn) was the artist for either one (see link below).

Feed Your Bonsai for Health & Beauty

Lush summer foliage and impressive deadwood are a big part of what makes this old Shimpaku juniper so exceptional. The lush foliage is the result of timely feeding coupled with good all around care. The photo is from our Masters Series Juniper book

Lush summer foliage and impressive deadwood are a big part of what makes this old Shimpaku juniper so exceptional. The lush foliage is the result of timely feeding coupled with good all around care. The photo is from our Masters Series Juniper book

Many people underfeed their bonsai. Especially beginners, where limited knowledge and lack of confidence can create hesitation or even a failure to act at all. This isn't always a terrible thing, at least in the short term, as it's possible to get carried away and feed too much. But if you're on the hesitant side, sooner or later you're going to need to fertilize your bonsai. That or stand by and watch it slowly decline

Rather than trying to write a whole treatise on fertilizing, I'm going to suggest you read Michael Hagedorn's Bonsai Heresy (see below). The whole book is well worth the time, however in this case (and once you have the book) you should turn to pages 153 to 199 and read carefully. Unless you already happen to be an expert, your knowledge will increase by leaps and bounds. And even if you are an expert, you'll still pick up valuable tidbits

You can bet that this luxurious crown is the result of timely feeding. This lush Kiohime Japanese maple belongs to Walter Pall, so I'm guessing that's his arm and hand. It (the tree not the hand) is 45 cm (18") high and more than 50 years old. It was originally imported from Japan. This photo and the one below are from Walter's blog

You can bet that this luxurious crown is the result of timely feeding. This lush Kiohime Japanese maple belongs to Walter Pall, so I'm guessing that's his arm and hand. It (the tree not the hand) is 45 cm (18") high and more than 50 years old. It was originally imported from Japan. This photo and the one below are from Walter's blog

Walter's maple after he reduced the crown and turned it around. Now the proportions are better and you can see the bones better too. This shape and crown will be maintained by proper feeding (more in the summer less in the spring on older trees) and skillful trimming. The pot is by Petra Tomlinson

Walter's maple after he reduced the crown and turned it around. Now the proportions are better and you can see the bones better too. This shape and crown will be maintained by proper feeding (more in the summer less in the spring on older trees) and skillful trimming. The pot is by Petra Tomlinson

This hornbeam belongs to Mario Komsta. I lifted it from an old Bark post (2010). It's a great example of a powerful trunk and an exceptional example of fine branching, the result of ample fertilizing and skillful trimming. Once the trunk and branching are well developed you can reduce or ever stop spring feeding but continue to feed in the summer (more on this in Bonsai Heresy)

This hornbeam belongs to Mario Komsta. I lifted it from an old Bark post (2010). It's a great example of a powerful trunk and an exceptional example of fine branching, the result of ample fertilizing and skillful trimming. Once the trunk and branching are well developed you can reduce or ever stop spring feeding but continue to feed in the summer (more on this in Bonsai Heresy)

Michael Hagedorn's Bonsai Heresy

Michael Hagedorn's Bonsai Heresy

The Bonsai book for experienced bonsai practitioners

who may need to unlearn a few things*

and for beginners who want to get it right the first time

*"It ain't ignorance causes so much trouble, it's folks knowing so much that ain't so"

Josh Billings

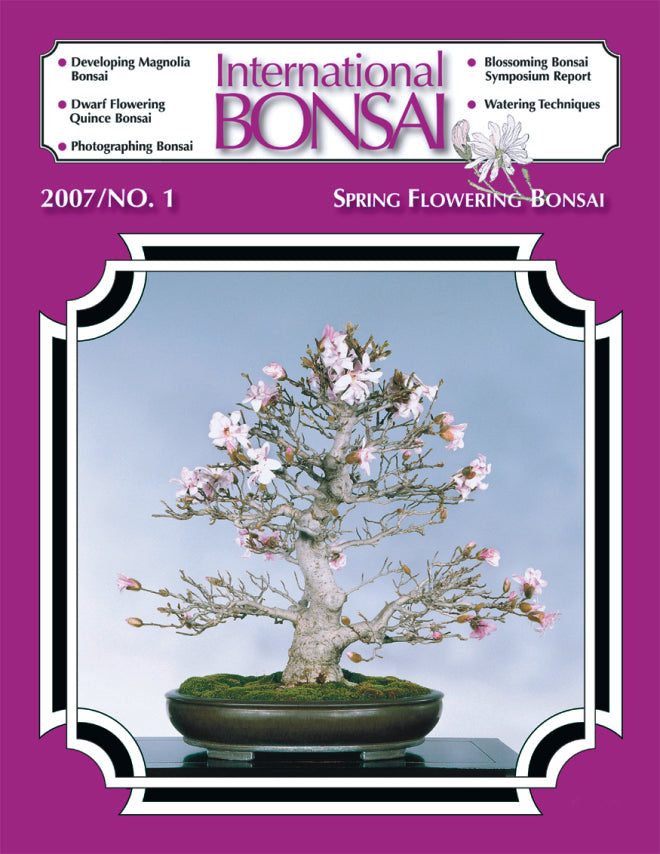

Bill's Blooming Bonsai and a Gentle Reminder About the Upcoming U.S. National

Today, we've got five deciduous Magnolias that belong to Bill Valavanis. Just in case you don't know Bill, he is the third inductee into the U.S. National Bonsai Hall of Fame as well as a masterful bonsai artist, scholar, publisher, nurseryman and of course, the founder and still prime mover of the U.S. National Bonsai Exhibitions

I spoke with Bill a while back and he was confident that this fall's show will go on. Personally, I hope it does, but much depends on where we're at with the pandemic

Continued below...

Continued from above...

As always it is being held in Rochester, NY and the dates this year are September 12-13. For details and to register and find lodging, go to Bill's International Bonsai site

If conditions allow, I look forward to seeing you there!

Bill's famous bonsai magazine. You can subscribe on his site

NEW! The Ultimate Bonsai Handbook - The Complete Guide for Beginners

The Ultimate Bonsai Handbook

Learn bonsai the traditional way with 70 types of trees and over 1,000 photos. Each step in the process of creating and maintaining bonsai is clearly illustrated by quality photos. This is in keeping with Show First, Tell Later, a superior way of teaching and learning almost everything

Continued below...

Continued from above...

This way is confirmed by Americans and other Westerners who have apprenticed in Japan. The master teaches by showing rather than wasting a lot of time trying to explain the process before you've even seen it done and perhaps tried to imitate it. Once you have the visual and even the kinetic experiences, words can be helpful and in this case, each photo is supported by a brief explanation. You might be surprised at just how well this works

Continued below...

Continued from above...

Continued from above...

Yukio Hirose is an internationally respected bonsai artist and teacher and this remarkable book is the result of years of teaching beginning and intermediate bonsai students. We highly recommend it

Continued below...

Continued from above...

The following is from the publisher's notes...

Written by one of Japan's foremost experts, The Ultimate Bonsai Handbook provides a complete overview of every aspect of bonsai gardening.

Over 1,000 photos demonstrate each step involved in raising and caring for 70 types of bonsai, supporting the book's "learn by imitation and observation" approach. This detailed book will serve as a timeless reference to cultivating pines, maples, flowering and fruit bearing trees and many other varieties.

This practical, comprehensive bonsai guide includes information about:

Types of bonsai and how to choose them

Basic tree shapes and how to display them

Tools, soils, and containers

Transplanting, root trimming, watering and fertilizing

Propagation, pruning, wiring and support

And much more!

About the Author:

Yukio Hirose fell in love with Bonsai at the Osaka World Expo in 1970 and has been devoted to growing, selling and teaching about bonsai ever since. He is the owner of Yamatoen Bonsai Garden in Kanagawa prefecture and is one of Japan's leading Shohin bonsai artists. An active instructor, Hirose offers workshops throughout Japan. He is an award-winning organizer of bonsai exhibitions and has served as the chair of the All Japan Shohin Bonsai Association.

The Ultimate Bonsai Handbook

The Ultimate Bonsai Handbook

ORDER YOURS NOW - ONLY 24.99

and while we're at it...

Two More NEW Bonsai Books

Bonsai Heresy by Michael Hagedorn

This is an absolute must read that will expand and deepen

you bonsai knowledge in ways you haven't even imagined

ORDER YOURS NOW - ONLY 24.95

The Little Book of Bonsai

The Little Book of Bonsai

Jonas Dupuich is one of our most knowledgable North American

Bonsai artists & teachers and this book is proof positive

of his bonsai and communications skills

ORDER YOUS NOW - ONLY 14.99

How did he do this? Because you can't see any soil, you might wonder if this one is a flowering air plant. Though no explanation (nor plant variety) is given, my guess is that there is a pocket of soil nestled out of sight in this piece of driftwood

How did he do this? Because you can't see any soil, you might wonder if this one is a flowering air plant. Though no explanation (nor plant variety) is given, my guess is that there is a pocket of soil nestled out of sight in this piece of driftwood  Here's Robert's caption with this one... "Nature holds the perfect key to aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual balance; breaking its balance will bring disaster!"

Here's Robert's caption with this one... "Nature holds the perfect key to aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual balance; breaking its balance will bring disaster!"

Robert's caption "Critics and curators are failed artists." A little harsh but being outspoken comes with the territory

Robert's caption "Critics and curators are failed artists." A little harsh but being outspoken comes with the territory

A metaphor for bonsai? You'll have to

A metaphor for bonsai? You'll have to  Robert with one of his unique creations

Robert with one of his unique creations

Bright yellow is a strong color, but I think this tree can handle it. The dense foliage and sturdy trunk are the keys. The artist is Tomohiro Masumi. No variety is given

Bright yellow is a strong color, but I think this tree can handle it. The dense foliage and sturdy trunk are the keys. The artist is Tomohiro Masumi. No variety is given

Another bright yellow pot and an even stronger trunk. Again no variety is given, but the leaves are easy to identify as Japanese maple...

Another bright yellow pot and an even stronger trunk. Again no variety is given, but the leaves are easy to identify as Japanese maple...

Another strong pot and another maple, though this time it's a Trident. You can recognize Trident maples by their three pointed leaves (thus the name). The impressive nebari has a distinctively Trident look as well

Another strong pot and another maple, though this time it's a Trident. You can recognize Trident maples by their three pointed leaves (thus the name). The impressive nebari has a distinctively Trident look as well

Is it just me, or do the color of the tree and pot together seem a little dissonant. Or perhaps a little dissonance isTomohiro’s intention

Is it just me, or do the color of the tree and pot together seem a little dissonant. Or perhaps a little dissonance isTomohiro’s intention

A white snake invasion, or just a bench full of Tomohiro Masumi's little trees (mostly junipers) with fresh lime sulfur?

A white snake invasion, or just a bench full of Tomohiro Masumi's little trees (mostly junipers) with fresh lime sulfur?

This planting from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic is quite similar to the planting on the cover (below): same trees (cryptomeria), same (or nearly the same) pot and somewhat similar rocky ravine separating two tree and moss covered areas. The main difference is that this one shows a deep ravine. The rocks that define it represent tall vertical cliffs

This planting from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic is quite similar to the planting on the cover (below): same trees (cryptomeria), same (or nearly the same) pot and somewhat similar rocky ravine separating two tree and moss covered areas. The main difference is that this one shows a deep ravine. The rocks that define it represent tall vertical cliffs

Front schemata. The pot is 27″ x 19″ (69cm x 48cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 29 cryptomeria that range from 4″ to 14″ (10cm to 36cm) tall and 9 river rocks. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use

Front schemata. The pot is 27″ x 19″ (69cm x 48cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 29 cryptomeria that range from 4″ to 14″ (10cm to 36cm) tall and 9 river rocks. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use  Bird’s eye view. Notice how the opening in front is off center and slants and curves as it goes back. If it were directly centered and straight it would appear contrived. Notice also how the ravine narrows and curves around and disappears from sight and then opens up into a pool. Viewed from the front, this creates a sense of mystery and the appearance that it just goes on and on into a vast landscape, rather than being restricted to a very finite pot

Bird’s eye view. Notice how the opening in front is off center and slants and curves as it goes back. If it were directly centered and straight it would appear contrived. Notice also how the ravine narrows and curves around and disappears from sight and then opens up into a pool. Viewed from the front, this creates a sense of mystery and the appearance that it just goes on and on into a vast landscape, rather than being restricted to a very finite pot

I found this old out-of-print classic* at Green Apple Books in San Franscisco for ten dollars (minus my family discount – see disclaimer below). It was in near perfect condition after more than forty years (now more than 50 years... copyright 196, Kodansha International). The original price was $6.95 (hardcover no less).

I found this old out-of-print classic* at Green Apple Books in San Franscisco for ten dollars (minus my family discount – see disclaimer below). It was in near perfect condition after more than forty years (now more than 50 years... copyright 196, Kodansha International). The original price was $6.95 (hardcover no less).  Koryo is the given name of this Japanese maple. No translation is given, but one possibility in 'consideration' as in 'worthy of consideration,' but that's just a guess on my part. Its estimated age is 120. The photo is from The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama, Japan

Koryo is the given name of this Japanese maple. No translation is given, but one possibility in 'consideration' as in 'worthy of consideration,' but that's just a guess on my part. Its estimated age is 120. The photo is from The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama, Japan  Koryo, a closer look

Koryo, a closer look

This Japanese black pine is called Seiran, which in this case it might be 'star.' Though if you really care, you might look up the Kanji (Omiya shows it) and do your own research. The estimated age is 120 years

This Japanese black pine is called Seiran, which in this case it might be 'star.' Though if you really care, you might look up the Kanji (Omiya shows it) and do your own research. The estimated age is 120 years

Seiran, a closer look

Seiran, a closer look

Seijaku is the name given to this Japanese white pine. Nothing came up in my cursory search under Seijaku, but looking at the Kanji given with Omiya's name, 'silence' might work (please don't take this to the bank, I don't read Kanji and can only guess)

Seijaku is the name given to this Japanese white pine. Nothing came up in my cursory search under Seijaku, but looking at the Kanji given with Omiya's name, 'silence' might work (please don't take this to the bank, I don't read Kanji and can only guess)

Seijaku's estimated age is 200 years

Seijaku's estimated age is 200 years  This Japanese black pine with its trunk fused to a rock is called Zuiko. You might want to do your own research (it's complicated). The tree's estimated age is 120 years

This Japanese black pine with its trunk fused to a rock is called Zuiko. You might want to do your own research (it's complicated). The tree's estimated age is 120 years

Zuiko, close up

Zuiko, close up

Saving the granddaddy for last. It's Japanese white pine called Uzushio with an estimated age of 500 years. There doesn't seem to be any ambiguity about the name... Uzushio means 'whirlpool'

Saving the granddaddy for last. It's Japanese white pine called Uzushio with an estimated age of 500 years. There doesn't seem to be any ambiguity about the name... Uzushio means 'whirlpool'

Whirlpool, close up

Whirlpool, close up

Here's a photo from a post we did in 2015 on this same tree. In that post I called it 'Whirlpool Dancer' (I'm not sure where I got the Dancer part). It is also featured in our Masters Series Pine book (see just below) in a chapter titled, 'Jewel to Whirlpool'

Here's a photo from a post we did in 2015 on this same tree. In that post I called it 'Whirlpool Dancer' (I'm not sure where I got the Dancer part). It is also featured in our Masters Series Pine book (see just below) in a chapter titled, 'Jewel to Whirlpool'

I think all three of the trees in this Penjing water planting above would qualify as bonsai on their own and there are some bonsai plantings that might share some rock features with this one

I think all three of the trees in this Penjing water planting above would qualify as bonsai on their own and there are some bonsai plantings that might share some rock features with this one

This one, which happens to one of my favorite Penjing plantings, seems even larger in scale as the one above and also has a couple human features that set it apart and enhances the feeling of a vast natural setting. These little human or human structure figurines (like boats and huts) are common in certain types of Penjing and much less common in bonsai, though you may see them in some saikei plantings

This one, which happens to one of my favorite Penjing plantings, seems even larger in scale as the one above and also has a couple human features that set it apart and enhances the feeling of a vast natural setting. These little human or human structure figurines (like boats and huts) are common in certain types of Penjing and much less common in bonsai, though you may see them in some saikei plantings

Lush summer foliage and impressive deadwood are a big part of what makes this old Shimpaku juniper so exceptional. The lush foliage is the result of timely feeding coupled with good all around care. The photo is from

Lush summer foliage and impressive deadwood are a big part of what makes this old Shimpaku juniper so exceptional. The lush foliage is the result of timely feeding coupled with good all around care. The photo is from  You can bet that this luxurious crown is the result of timely feeding. This lush Kiohime Japanese maple belongs to Walter Pall, so I'm guessing that's his arm and hand. It (the tree not the hand) is 45 cm (18") high and more than 50 years old. It was originally imported from Japan. This photo and the one below are from Walter's blog

You can bet that this luxurious crown is the result of timely feeding. This lush Kiohime Japanese maple belongs to Walter Pall, so I'm guessing that's his arm and hand. It (the tree not the hand) is 45 cm (18") high and more than 50 years old. It was originally imported from Japan. This photo and the one below are from Walter's blog Walter's maple after he reduced the crown and turned it around. Now the proportions are better and you can see the bones better too. This shape and crown will be maintained by proper feeding (more in the summer less in the spring on older trees) and skillful trimming. The pot is by Petra Tomlinson

Walter's maple after he reduced the crown and turned it around. Now the proportions are better and you can see the bones better too. This shape and crown will be maintained by proper feeding (more in the summer less in the spring on older trees) and skillful trimming. The pot is by Petra Tomlinson This hornbeam belongs to Mario Komsta. I lifted it from an old Bark post (2010). It's a great example of a powerful trunk and an exceptional example of fine branching, the result of ample fertilizing and skillful trimming. Once the trunk and branching are well developed you can reduce or ever stop spring feeding but continue to feed in the summer (more on this in Bonsai Heresy)

This hornbeam belongs to Mario Komsta. I lifted it from an old Bark post (2010). It's a great example of a powerful trunk and an exceptional example of fine branching, the result of ample fertilizing and skillful trimming. Once the trunk and branching are well developed you can reduce or ever stop spring feeding but continue to feed in the summer (more on this in Bonsai Heresy)